A Student From a Low-income Household Is an Example of What Type of Correlate of School Failure

Wealthy families do not worry about food, or transportation, or whether walking to school involves crossing a gang boundary.

In This Lesson

How is poverty measured?

How are poverty and education related?

Who gets a free school lunch?

How does race affect test scores?

What is the definition of poverty?

How does poverty affect learning?

★ Discussion Guide.

They have shelter, and health care when they need it. If a crisis hits, they have savings to fall back on – or at least access to credit on reasonable terms.

If you haven't lived in poverty, it is hard to imagine it.

How are poverty and education related?

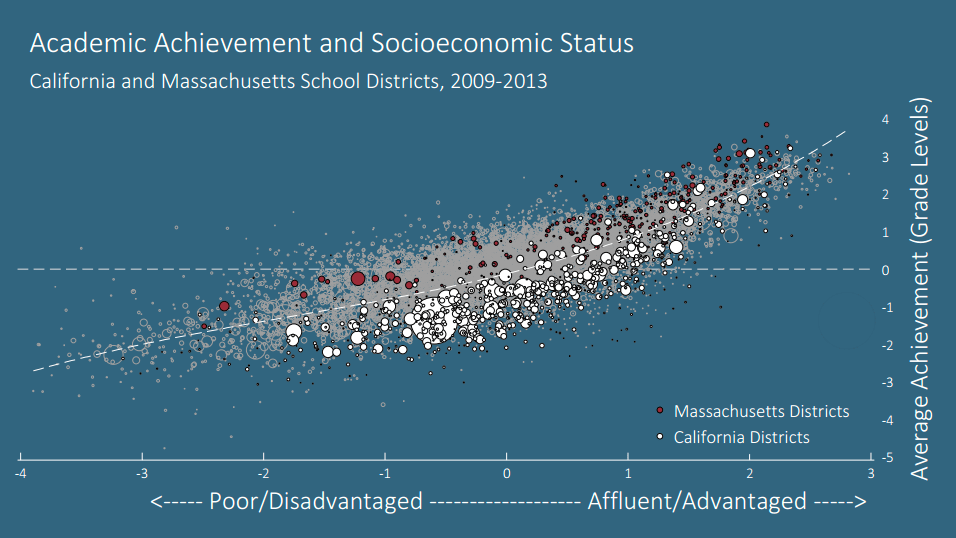

Poverty correlates very strongly with academic results. Schools with low test scores nearly always have a lot of families living in poverty. Schools without a lot of poverty nearly always have good scores. This correlation is very stable. For example, the chart below shows scores on the NAEP test, highlighting districts in Massachusetts and California. On this chart, up is good — clearly, students at any level of poverty tend to do better in Massachusetts... but it makes an even bigger difference to have less poverty.

Schools where many students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch ('FRPL' in edspeak) tend to have lower scores than those where families are wealthier. Across the wealth spectrum, scores in California districts lag substantially behind those in Massachusetts. (Chart: Sean F. Reardon from 'The Landscape of US Educational Inequality')

Schools where many students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch ('FRPL' in edspeak) tend to have lower scores than those where families are wealthier. Across the wealth spectrum, scores in California districts lag substantially behind those in Massachusetts. (Chart: Sean F. Reardon from 'The Landscape of US Educational Inequality')

The connection between poverty and education results is one of the most enduring relationships in all of education research. It shows up everywhere. For example, there are predictable gaps in the scores of the ACT tests that students take as part of the college application process. In a 2015 chart from a multi-year study, ACT identified a set of benchmarks to compare how well students are prepared for college and career. While 42% of students from families with incomes above $100,000 met all four ACT College Readiness Benchmarks, only 13% of low income students (under $36,000) did.

In 2017 the gap showed up, as usual, in the results of California's annual standardized test, the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP). About 2/3 of students from low income families did not meet grade level standards in English Language Arts/Literacy. For students not in low income families the ratio was flipped — about 2/3 did meet grade level standards. The relationship to poverty is amplified at the extremes. For example, about a third of students from a family not living in poverty scored in the "exceeded standards" range. But only one in ten students from a low income family did so.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) studied a group of tenth-grade students from families with different family income or "socioeconomic status" (SES) over a ten-year span. The results are summarized in this video:

Most poverty statistics depend on lunch

Poverty statistics in education often rely on a crude definition of poverty: whether a student's family qualifies for the free lunch program. This is a useful distinction, but sloppy. You either qualify or you don't. This leaves room for big differences. It's like calling both Tom Cruise and Danny Devito "short." Sure, neither should be cast as a star player in a movie about basketball, but they don't equally miss the mark, right?

About half of California students qualify for the lunch program. Matt Chingos of the Brookings Institution cautions that this is not the same as saying that half of California students are in poverty. The rules for meal programs vary from one place to another, and even from school to school. Over time, the requirements to qualify for food aid have generally been made less stringent, which can create the impression of rising poverty even in places where it is declining. A growing number of schools simply provide lunch to everyone, eliminating the paperwork hassle and possible shame involved.

To qualify for free or reduced-price lunch usually requires filling out some forms, a small but nevertheless important barrier. Not every child who theoretically qualifies for food aid gets it. Schools and districts in high-poverty areas put some effort into getting the paperwork filled and filed because there is significant money at stake: under California's funding system districts receive extra funding to support the education of students in need.

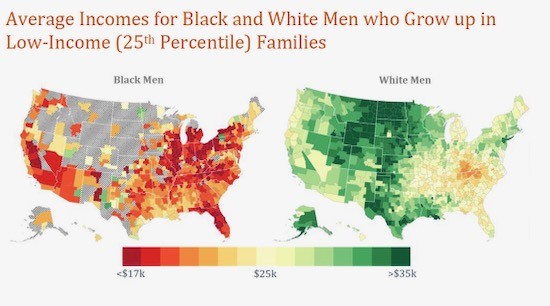

Discussions about the "achievement gap" often focus on differences in student achievement based on ethnicity, and for good reason. Poverty and ethnicity are strongly correlated in California, as they are elsewhere. African American and Hispanic students are much more likely to be poor and their parents often have less education than white and Asian students. Moreover, the intergenerational income gap across races persists over time. For example, throughout the US, black boys in almost all neighborhoods earn less in adulthood than white boys growing up in families with comparable income.

Poverty in California: Much Worse than Average

The challenges of poverty are great everywhere, but they are particularly stark in California.

According to a 2018 report from California Budget and Policy Center, the cost of housing has exploded in California, and wages have not grown as fast as the price of rent. The effect on families has been dire: poverty hurts kids, and an increase in poverty is correlated with all kinds of bad outcomes. Families living on the edge find it harder to provide their kids with good spaces and places to focus on learning. The chart above compares the supplemental poverty rate in each state. (Statisticians prefer this measure to the conventional poverty rate because it is more comprehensive and meaningful.)

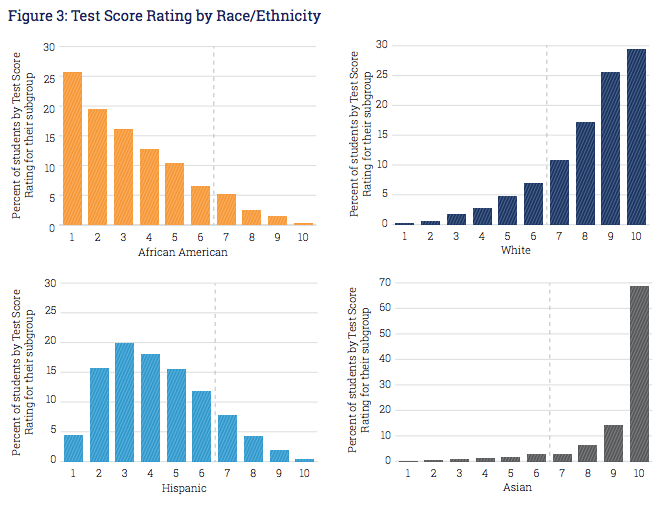

Achievement gaps part 1: Race

Race correlates with test scores and other outcome measures like high school completion or college completion. The effects are not just attributable to poverty.

For example, in a 2015 study of the SAT scores of more than a million students attending the University of California, sociologist Saul Geiser found a strong pattern:

"Socioeconomic background factors – family income, parental education, and race/ethnicity – account for a large and growing share of the variance in students' SAT scores over the past twenty years. More than a third of the variance in SAT scores can now be predicted by factors known at students' birth, up from a quarter of the variance in 1994. Of those factors, moreover, race has become the strongest predictor of students' SAT scores. Rather than declining in salience, race and ethnicity are now more important than either family income or parental education in accounting for test score differences."

Race shows up in patterns in other studies, too, such as the international PISA exam:

The graph above interposes international test data with American PISA test scores disaggregated by race/ethnicity. This view underscores the reality that US test scores have much to do with the history of American immigration. There are many theories about root causes of this correlation, some of them frankly racist. But racist theories of differences in student achievement collapse in the face of closer examination of facts. For example, a 2018 analysis points out that recent sub-Saharan African immigrants consistently out-perform other definable immigrant groups in measures of educational attainment.

Scholars including Harvard's Ronald Ferguson and Stanford's Linda Darling-Hammond have tackled the complex issues of race in education. Some of the most frequently cited sources of patterns in the educational achievement of groups include hidden underinvestment; variances in family "social capital"; persistent cultural effects; and various effects of racism including race-based differences in expectations.

GreatSchools.org collects data about schools, examining student demographics and student outcomes including test results. In a 2017 report, Searching for Opportunity: Examining Racial Gaps in Access to Quality Schools in California, the organization focused attention on the small number of schools with a record of success for African-American and Latino students. The introduction to the report expresses the gap plainly:

"Only 2% of African American students and 6% of Hispanic students attend a high performing and high opportunity school for their student group, compared with 59% of white and 73% of Asian students."

The GreatSchools report shows that few Latino and African American students attend schools where students like them score well. Few Asian or white students attend schools where students like them score poorly. Few, however, is not the same as none. The report goes on to identify 156 high-performing "spotlight schools" where African-American and Latino students score highly. These schools, half of them with relatively high poverty, show what's possible.

Achievement gaps part 2: Poverty

John Scalzi, author and social commentator, has suggested a provocative analogy to support discussion about the roles of race, gender, class and sexual orientation in education and life. He imagines life as a video game in which the difficulty setting is determined by your demographics. "In the role playing game known as The Real World," Scalzi proposes, "'Straight White Male' is the lowest difficulty setting there is... the 'Gay Minority Female' setting? Hardcore."

Writers and researchers take many approaches to exploring the patterns that connect with outcomes in education and life. The following video examines different educational and life outcomes of two children born into different neighborhoods.

Definitions of povery matter

Researchers define poverty in different ways, and states have some influence over the definitions. For example, is a family counted as poor if it falls below a certain income level, or must it remain below that level for an entire year? What if it falls only a tiny bit below or above the line?

There is no single, canonical meaning of poverty — context matters. Economics professor Sendhil Mullainathan has amassed evidence that scarcity itself taxes the mind. It's not just that bad decisions make people poor, this work suggests: "Instead, people make bad decisions because they are poor." Poverty creates its own negative feedback loop.

Many theories of change in education seek to identify what combination of factors, in terms of students' experiences both in and out of school, cause poverty and ethnicity to correlate so strongly with learning. Some of those factors are explored in the next few lessons.

Updated April 3, 2017. Added chart comparing scores in California and Massachusetts.

Updated May 8, 2017 to fix a grammar error caught by a reader. (Thanks, April!)

Updated Oct, 2017 with new CAASPP test results and new info about the hazards of using school lunch to measure poverty.

Updated Jan, 2018 to incorporate information about African immigrant achievement and the GreatSchools "Searching for Opportunity" report.

Updated Sep, 2018, adding video from NCES.

Updated Jan, 2020 with link to blog post about homelessness.

Updated extensively in December 2020.

A Student From a Low-income Household Is an Example of What Type of Correlate of School Failure

Source: https://ed100.org/lessons/poverty

0 Response to "A Student From a Low-income Household Is an Example of What Type of Correlate of School Failure"

Enviar um comentário